WARNING: This post contains photographs of a little naked plastic man.

Okay, you’ve been warned.

I want to discuss an important concept that most every approach to drawing the imagined figure mentions, variously called a plumb line, gravity line, axial line, or central axis. Simply put, this is an imaginary line that runs the length of the figure from top to bottom, helping an artist position the parts of the body in relation to one another.

In a side view, for instance, if we know how certain features in the head should align with other landmarks on the body—from the shoulders, waist, and hips, right down through the legs and feet—an axis can help us to line up these features (literally). In the front and rear views of the figure, an axis helps us draw the figure with symmetry between the right and left halves.

Unfortunately, most books lead the reader to think of the axis as floating in front of the figure. Many artists also make this assumption, probably from the habit of using a sighting tool (such as a pencil or dowel) to line up parts of the body when drawing from a live model. In imagined drawing, however, it’s better not to think of this axis as being in front of the figure, but as running through the figure—skewering it, if you’ll pardon the disturbing image.

For this reason, the StArt System refers to this line as the core axis of the figure. The core axis is a starting point for many drawings within the StArt System, especially those of standing poses with the figure at rest, as demonstrated in this tutorial on drawing the static standing pose. Think of the core axis as running through the body, and it will provide a constant reference for drawing the figure from multiple views.

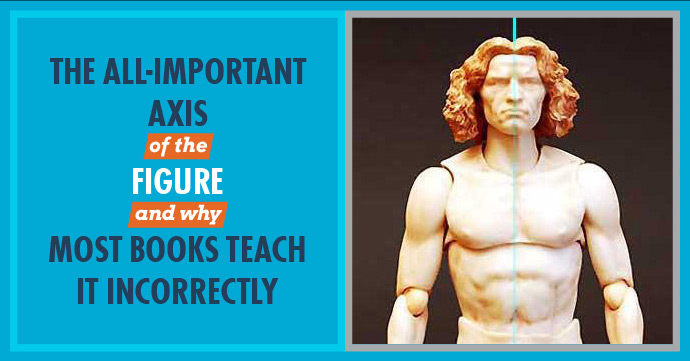

Fig. 1. In the symmetrical front view of the figure, the core axis runs through the midline of the body.

A Question Not So Easy to Answer

Let’s look at some examples to help understand this concept. These photos feature the Vitruvian Man action figure, an amazing model from the Figma Series by Max Factory × Masaki Apsy, and based on Leonardo da Vinci’s famous drawing of the same name.

In the symmetrical front view of the figure (fig. 1), the location of the core axis is easy to identify, as it runs through the midline of the body. This would be true from the rear view, too. But if the axis lies at the core of the figure, how deep within the body (that is, how far back in space) is it in these views?

When we examine the figure from the side, we can see why this question is not so easy to answer. In the asymmetrical side view, there is no obvious midline, and therefore no definite place where we can say the core axis passes (fig. 2).

Books on figure drawing vary in where they place the axis in the side view. In fact, there is no one correct position for the side-view axis, nor is there any correct alignment of features. In reality, the alignment of the body when viewed from the side differs greatly from person to person.

For artists, what matters most is that the location of the side-view axis makes practical sense from a drawing standpoint. That is, it should:

- Result in an accurate drawing of a figure with good posture.

- Align with certain features of the body so as to be easy to learn and remember.

The Core Axis in the StArt System

The StArt System achieves both of these objectives by placing the core axis at a depth about halfway back on the head, from which it descends through the body (fig. 3). This location aligns vertically with a point on the ground between the arches of the feet, about halfway between the heels and the toes.

In this article, I won’t discuss the different features it intersects along the way—we’ll come back to that topic in the tutorial for drawing the figure from the side. Suffice to say, if an artist learns one “master” location for the placement of the axis in the side view and the bodily features it connects, it’s an easy matter to deviate from this location to draw people with different postures or body types.

When we cross-reference the position of the core axis from the front view with its position from the side view, we can begin to understand how it penetrates the figure three-dimensionally. To see this clearly, however, we need to examine the figure in three-quarter view.

Fig. 4. In the three-quarter view, it is more apparent how the core axis runs through the body rather than floating in front of it.

In figure 4, it’s apparent how the core axis descends from the crown of the head, passes through the torso and hips, and emerges from between the legs to drop to the floor. Notice how, in the front, side, and three-quarter views, the core axis consistently hovers over the same point on the floor, where the diagonal lines intersect.

Advantages of the Core Axis

For the artist, there are multiple advantages to thinking of the axis as passing through the body rather than floating in front of it. Because the core axis is in a constant location between the arches of the feet, it provides a fixed line around which the body rotates. By having certain constants that apply to different views and poses of the figure, learning to draw the figure from multiple views and in various poses becomes much easier.

Likewise, in drawings of the figure within an environment (especially surroundings drawn in perspective), it is easier to place and scale the figure correctly using a core axis.

When applying proportional systems such as those based on the height of the figure’s head, measuring head-length units along the core axis is more accurate than measuring in front of the figure. We can even conceive of a proportional grid that cuts through the body at the position of the core axis. This offers a more consistent set of proportions for drawing the figure from different views, as in a sequence of drawings.

Some of these advantages—and others as well—will become apparent as you draw the imagined figure in more and different ways. For now, begin to shift your thinking about axis lines in drawing, conceiving of them as passing through the figure rather than floating in front. The benefits will grow with every drawing.

Leave a Reply